OK, last time I gave you a rundown of the ownership of the Roddye property through the years (specifically narrowing down to the 28 acres where the house now sits). Today, we’ll talk about the founding Russellville.

Our little town was named either for George Russell, the colonel’s friend and father-in-law, or for the entire Russell family, and it’s pretty certain that James Roddye was behind the choice of that name. Roddye married Russell’s daughter, Lydia, either just before or just after King’s Mountain, while both were still living in the Watauga settlements. After King’s Mountain, Russell and Roddye were among the men who came looking for land further west and landed in our area.

Roddye’s land grants are all along Bent Creek, which puts him in what’s now Whitesburg, and Russell’s were along Fall Creek, which plants him in what we call Russellville (I have seen one or two mentions of “Russelltown” in some really old documents, but apparently it was the ville that won out).

I’m not altogether certain that George Russell ever lived here. He was living across the river in what’s now Grainger County (German Creek, to be specific) fairly early on, and the documentation we have says the Roddye built his house in 1783, which is the same year that both men applied for their land grants.

Now, applying for the grants and actually having them officially recorded in the deed book sometimes took quite some time. The reasons for that involve the time it takes to send a surveyor out to do the official survey, come back and record it, which takes people to handwrite them into the deed book, along with copies of the deed and survey for the new “owners.” And there were a lot of them. The Europeans were grabbing as much Cherokee land as they could and making a fortune selling it to other Europeans, all the while heading out to force the Cherokee further and further away from their newly grabbed land. It takes a lot of time, all on horseback or foot.

So Russell’s Fall Creek grants, applied for in what was then Greene County, North Carolina, moved next (and very briefly, since it didn’t make it to actual state-ness) to the State of Franklin. The deeds were finally written into the deed book in 1787, still in the not-really-real Franklin and also North Carolina at the same time. At about that time, William Armstrong’s land around his Stoney Point and some acreage around it, including Roddye’s and Russell’s, ended up in the newly formed Hawkins County, North Carolina. So the deeds are transferred to the new county seat, Rogersville, and the following year – 1788 – the idea of Franklin bit the dust forever.

Meanwhile, Russell has sold the Fall Creek properties to Roddye for 300 pounds. That deed is recorded in Rogersville in 1790, and at about that time, North Carolina cedes the territory west of the Appalachians to the US government, and it become the Territory South of the Ohio River. Two years later, Jefferson County is formed, and our area falls into that county. Four years after that, the territory south of the Ohio is admitted to the union as the 16th state, Tennessee.

Whew. Once Tennessee is a state, Roddye got really busy buying and selling. He even briefly disappears from his Jefferson County lands in the early 1800s. I once thought he may have gone down to Rhea County, where his son Jesse had gone, but it appears that instead he went to Claiborne County, where he operated a ferry over the Powell River on the Kentucky Road as well as a tavern. He was there for a few years before returning to Russellville, where he owned most of what eventually became “downtown.”

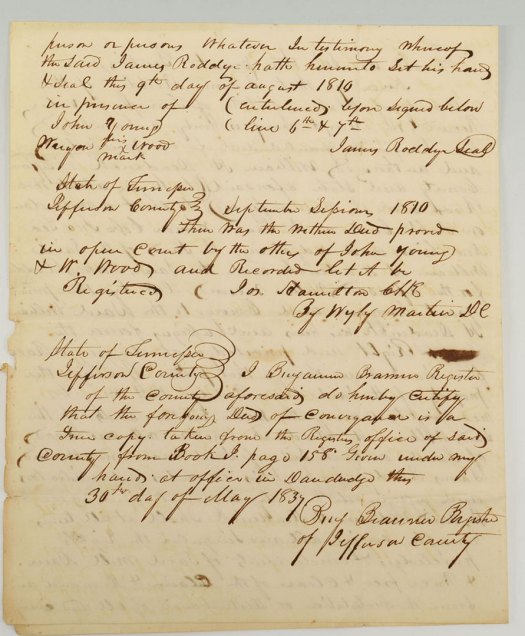

In 1810, he gave William H. Deaderick, a Hawkins County doctor, a deed to build a dam on Fall Creek and a mill race to cross Roddye’s property for a mill the good doctor built on his own property, adjacent to Roddye’s. It must have been around this time that Roddye and Deaderick began talking about the idea of an actual town.

In about 1819, the two men created a plan for said town. I’ve not found that plan yet, but I’m still searching. I know there was one because it’s mentioned in the official act to create the town of Russellville, which we’ll get to shortly.

Meanwhile, from about 1819 forward, Roddye and Deaderick are involved in selling land along what they call the Cross Roads Street – what we’ve known as Russellville Pike, Main Street, or just the old road. Deeds show that there were 18 “town lots” created along Cross Roads Street, each 1/4 acre. Some of them have alleys between them. Here’s a very rough sketch of those lots (not to scale!!!):

Somewhere I wrote down the size of the lots, but just now I can’t find it. They were about 60 feet by 160, but please don’t quote me on that. Fall Creek ran probably through lots 1 and 3 on the east side of town, which were owned by Roddye. Deaderick owned 2, 5, and 6, so the 1810 deed gave Deaderick the right to run a mill race across Roddye’s property to reach his mill, probably on lot 5 or 6. I say that because Deaderick later sold lots 5 and 6 to Patrick Nenney, and the mill race is mentioned in those deeds – which also leads me to believe that the Nenney House/Longstreet Museum probably sits on the back side of those two lots (the old town lots of Russellville got further chopped up in the 1910s when the Russellville Land Company bought up most of the Nenney property and sold it with a new layout).

Anyway, there’s a lot of buying and selling of the town lots during this time, and Roddye’s son Thomas continues that after his father’s death in 1822. Since Roddye and Deaderick had created this plan, I have to believe that they were working to get the Tennessee legislature to officially create the town of Russellville. Maybe there’s even correspondence about this somewhere. But we do know that in 1826, the legislature finally did just that, establishing the town (citing Deaderick and Roddye as the ones who laid out the plan) and naming “commissioners,” who may or may not have ever met, but they certainly had the right to do so.

The commissioners were William Felts, who owned a tavern probably on lot 3 (which later became the Riggs Tavern), James Phagan, James L. Neal, John Cox, and Joseph Austin. Another maybe, but maybe somewhere there’s correspondence about these commissioners and what they may or may not have done in their official capacity.

Oh – there’s also the handwritten bill creating the town of Russellville. You’ll see on the third page the notations about all the readings in the Tennessee House and Senate before it’s officially passed, signed by the governor (William Carroll), and recorded in The Acts of Tennessee:

Obviously, Russellville ended up being just a little village, with no commissioners. I have not yet found anything in the Acts of Tennessee disestablishing the town, so I can’t say how that may have come about. It was a bustling little town for a while, though, right up through the establishment of Hamblen County in 1870 and into the 20th century.